The region of Apokoronas is delimited to the south by the imposing massif of the White Mountains, with its lower offshoots, the mountains of Malaxa, curving round to the west. The massif descends gently into ranges of hills. Next comes a wide plain, rising up again into a semi-mountainous zone and ending at the sea via three large, flat openings, two in Suda Bay and one on the eastern boundary of the region. There are major springs in the area, while five rivers cross large parts of it and flow into the sea. One of the largest natural lakes in Crete, Lake Kournas, is located near the village of Kournas.

-

-

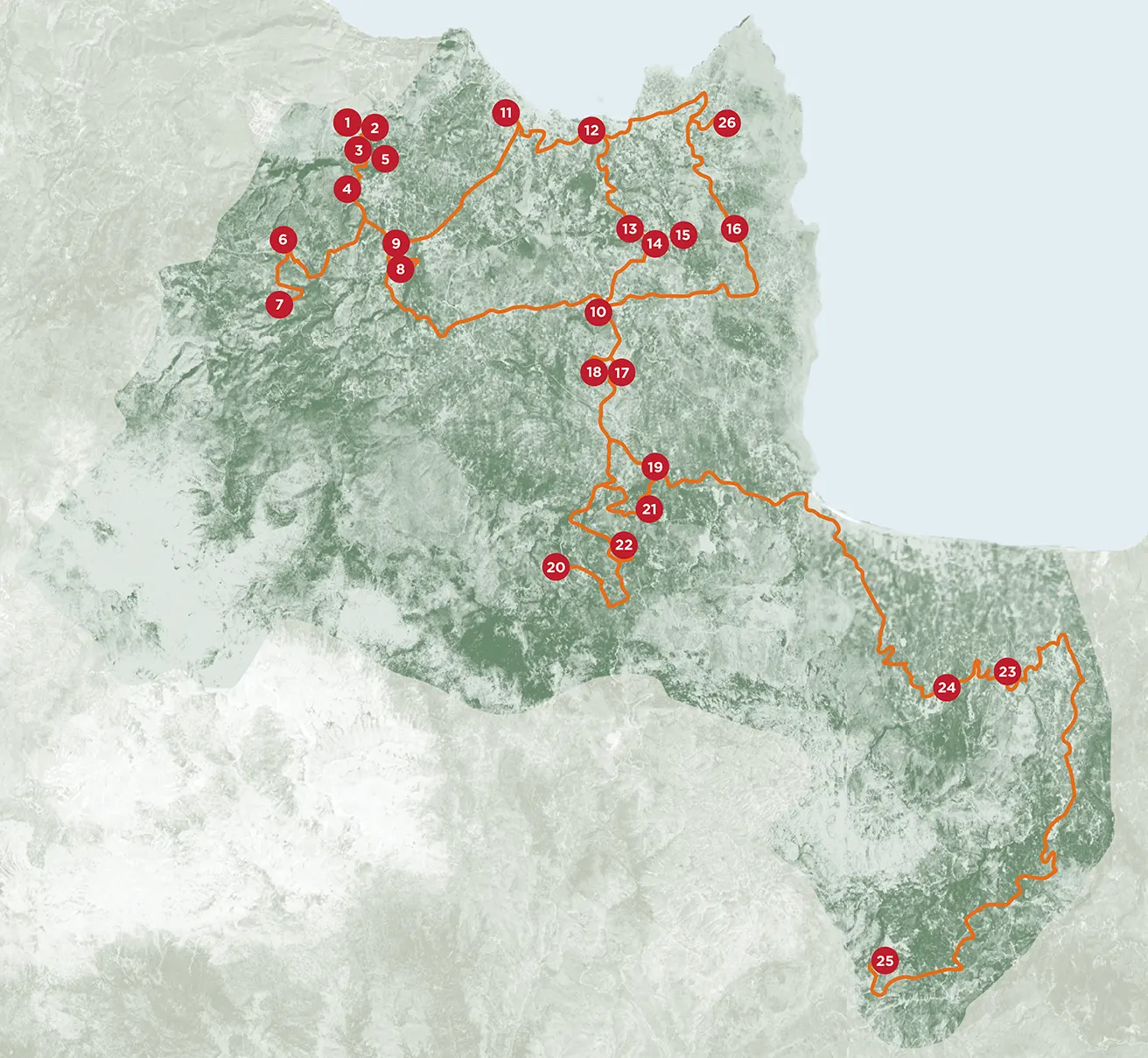

Map of Apokoronas with the White Mountains to the south and Suda Bay in the north (source: Google Earth).

-

-

Suda Bay. Map by G. Corner (1625). To the SE are the rivers of Apokoronas and the plain of Stylos, bordered on the south by the foothills of the White Mountains (source: Michalis Andrianakis, Fortifications in Crete (Part 3): Fortifications in Crete during Venetian rule (1204-1669), https://tinyurl.com/yeyvxx6k

A key factor in the development of Apokoronas through the ages has been its geographical position near the natural harbour of Suda and on the main north road of Crete. Its terrain is also an important feature of the region.

Archaeological research has shown that the fertile plain of Stylos, as well as the surrounding semi-mountainous areas such as Samonas, have been inhabited since at least the Early Minoan period (2800-2100 BC). From the Late Minoan period onwards, the second-largest centre of the Chania region after Kydonia flourished here. In the wider environs of Aptera (the A-pa-ta-wa of the Minoan tablets), near Stylos, was found one of the three known tholos tombs of Chania Prefecture. One of the few pottery kilns of the Late Minoan period on the island was discovered in the same area. The kiln and other finds confirm the importance of the settlement. The Stylos settlement is thought to be the Minoan city of Aptera, due to the absence of any earlier finds on the site of the city of historical times. Another Minoan settlement has been identified and partially excavated at a rural site near the village of Samonas. Its layout in neighbourhoods and its architecture are reminiscent of the later rural houses of Crete. The two-storey megaron-like building previously excavated there was probably the residence of the local ruler.

Many sites have been discovered in the wider area from Samonas to the national road at Kalami, where the vessel with the “lyre-player”, attributed to the Kydonian pottery workshop, was found in a tomb. Late Minoan pottery has also been found in caves in Kokkino Chorio and Kefalas, while there is yet another site in Souri. A very important tholos tomb of the same period, containing significant finds, was excavated in the countryside near the village of Fylaki.

The large plain of eastern Apokoronas with its many waters seems to have been another important centre of the period.

Aptera, built on a naturally fortified site from which it controlled the road between East and West Crete and the port of Suda, flourished during the historical period. The city had two harbours: Minoa, in what is now Marathi, and Kissamos on the coast of Kalyves, perhaps on the site of the later Castello Apicorno on the Kasteli hill east of the town, where antiquities have come to light. The archaeological evidence so far dates from the Geometric period. Aptera continued to prosper in Early Christian times. It was destroyed by an earthquake in the 7th century AD and lost all importance as a city after the devastating Saracen raids in 823

-

-

Ancient Aptera. Aerial photograph of the archaeological site from the SW (source: Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania, https://ancientaptera.gr/media-gallery/).

The remains of a settlement of historical times have also been discovered in nearby Stylos, which continued to flourish in the following periods. In the coastal zone, apart from the city of Kissamos, which should probably be sought in Kalyves, the ruins of Phoenix or Tanos have been identified at the site of Finikias, west of Almyrida. Greco-Roman remains have also been found on the islet of Karga. On the coast of eastern Apokoronas lay the cities of Amphimala and Hydramia, identified by investigations of recent years, the former in the village of Georgioupoli and the latter in the wider coastal zone near the River Mouselas. At the Kavousia site between Nippos and Fre are the remains of an ancient town, probably Hippokoronion, from which Apokoronas may take its name. Finally, an important ancient monument that has marked the course of the north road of Crete for centuries is the “Greek Arch”, the bridge between Maza and Vryses.

-

-

Hellenistic bridge, Maza. View from the SW (source: Maria Andrianaki).

The region of Apokoronas continued to prosper during the Early Christian period. Further east, near the small coastal village of Almyrida, on the edge of the Phoenix archaeological site, a large Early Christian funerary basilica of the 6th century was discovered. The existence of another basilica on the hilltop of Finikias shows that this was quite a large settlement. Basilica A at Almyrida is richly decorated with mosaic floors.

-

-

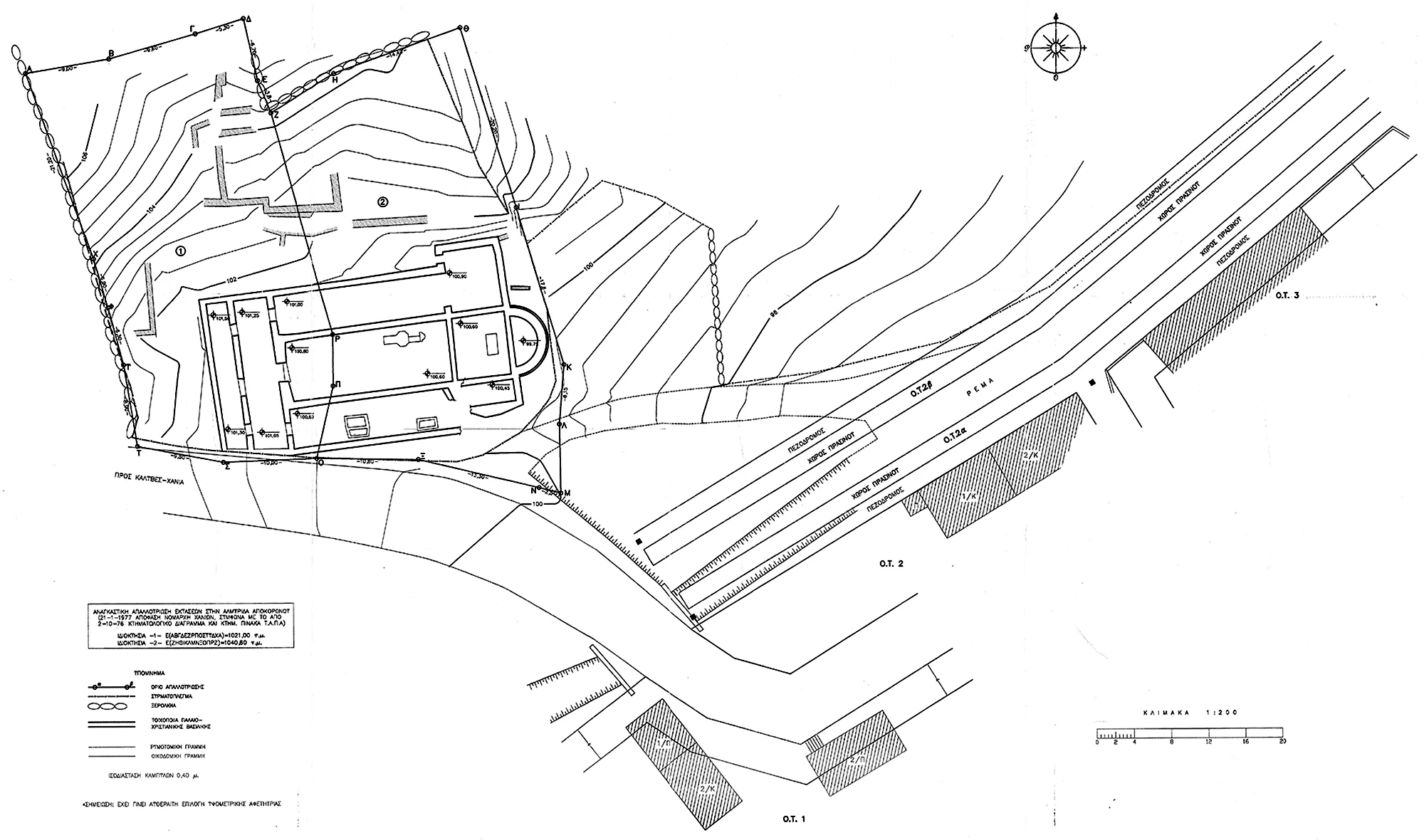

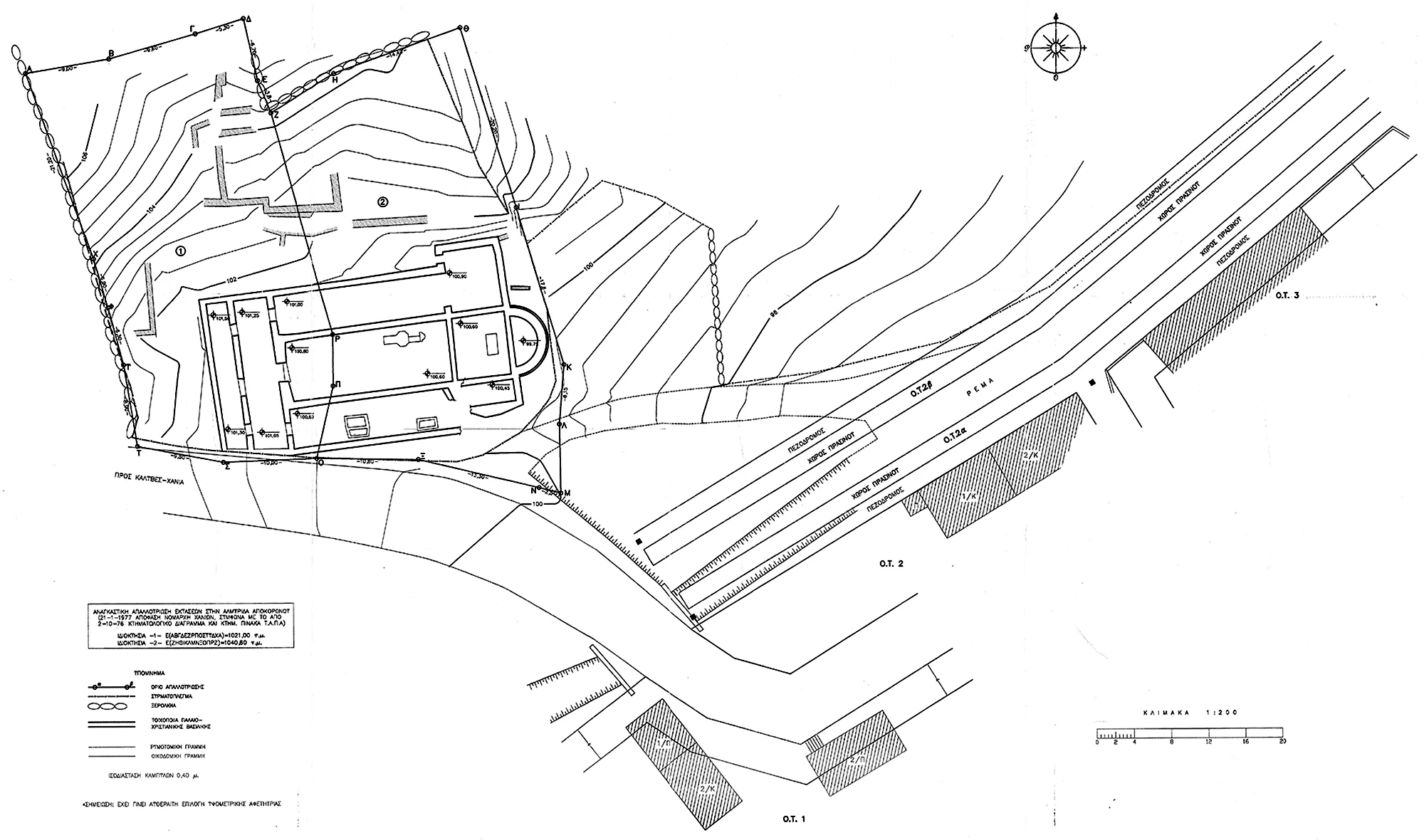

Basilica, Almyrida. Topographical plan including the church (source: Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania).

Until the period of Arab rule, the ancient settlements continued to flourish in the familiar form of the city-state. The coastal areas also experienced strong growth, due to the opportunities they offered for trade and communication with other regions. This form of development lasted as long as there was relative security. These conditions came to an end with the Arab invasions of the 7th century. The raids on the coast of Crete from the 7th century onwards and during the period of Arab rule on the island (823-961) caused significant changes in the settlement pattern of Crete, including, of course, in Apokoronas. The coast was abandoned as unsafe and new settlements were established inland, from the post-Arab period until the Venetian occupation of the area in the mid-13th century. The region of Apokoronas was known as the Turma of Psychro. Ecclesiastically it was subject to the See of Kalamonas. According to the sources, the area of Psychro remained the property of the imperial crown (according to one theory, the later name of the province may be linked to its dependence on the Byzantine crown: apo “from” + korona “crown” = Apokoronas). A huge tract of land, extending from Keramia and the deserted Aptera, Kamboi and the village of Stylos, to Samona, Ramni and the boundary of the River Kyliaris, was granted to the Monastery of St John the Divine of Patmos. Numerous documents from the monastery archives provide us with information on the area, the place-names (most of which still exist today) and the importance of the Dependency of Crete to the economic and cultural life of the monastery, as it seems that many of its surviving icons and relics came there via Stylos.

Important information from this period up to the 16th century is provided by the excavation around and inside the church of St John the Divine in Stylos, which belonged to the Monastery of Patmos. In the middle of the olive grove of Stylos stands the church of Panagia Zerviotissa (or Monastira), built in the 11th or 12th century. This is one of the most important Middle Byzantine churches of Crete in terms of architecture, showing the strong influence of Constantinople on Cretan architecture during the Second Byzantine period. Its construction seems to be connected with the activities of the Monastery of Patmos.

-

-

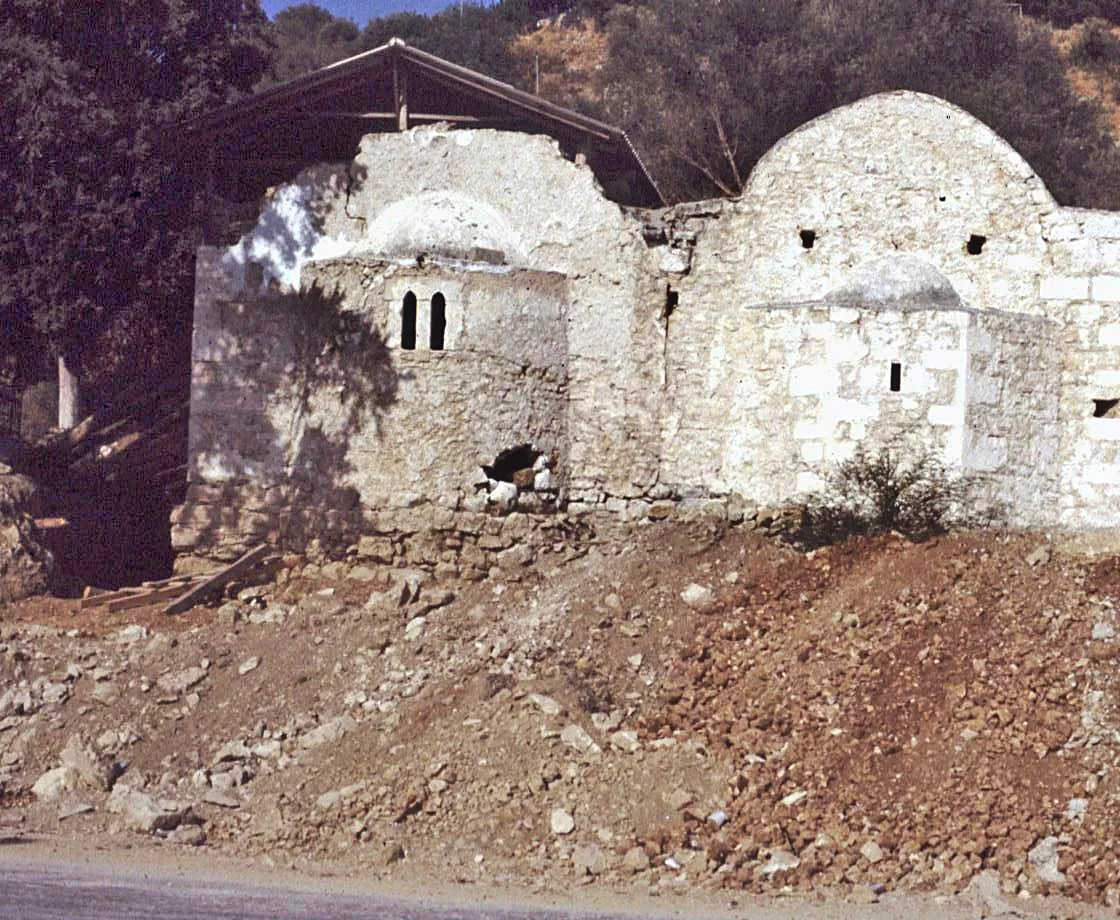

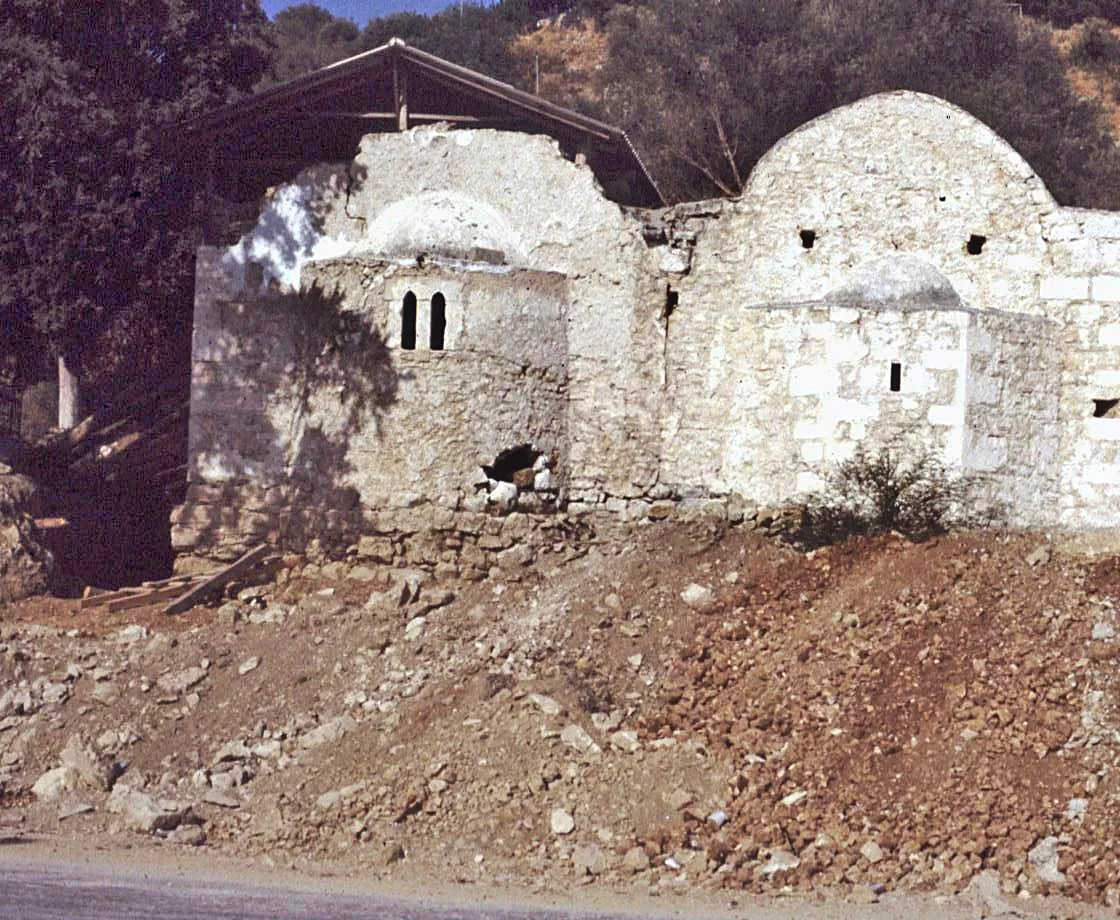

SS John the Divine and Nicholas in Stylos, Stylos. The churches during restoration work (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

-

-

Panagia Zerviotissa, Stylos. The church prior to its restoration (1984) in the midst of the olive grove (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

Higher up, in Kyriakoselia, the church of St Nicholas appears to have been built in the first millennium, based on various archaic building features. The church of St George in Kournas dates from the late 12th century. It is a three-aisled, timber-roofed basilica with a narthex, not a particularly common type in Crete. The building is of relatively simple construction, but the fragmentary frescoes are excellent examples of Late Komnenian art.

-

-

St George, Kournas. The west front of the church (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

The surviving churches of the Second Byzantine period in Apokoronas reveal a high level of culture, indirectly confirming the region’s links with Constantinople and the Monastery of Patmos, which was directly connected to the imperial city. There may be a link with the strong tradition and indirect information on the “Twelve Noble Families” of Constantinople, who were sent to Crete at an unspecified date in obscure historical circumstances, and constituted a sort of feudal class.

At the beginning of the 13th century, Crete came under Venetian rule following the Sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 and the subsequent distribution of the territories of the Byzantine Empire. The Venetians only managed to conquer Chania much later than the rest of Crete, due to the greater opposition they encountered from the local population. The conquest was completed in 1252 with the installation of Venetian colonists in the city of Chania, on the site of ancient Kydonia, and the distribution of rural estates among them.

The reaction of the local population led by the local lords and the Orthodox clergy, with the assistance of the Empire of Nicaea – established by exiled Byzantine aristocrats – was fierce and long-lasting, with constant rebellions. The rebuilding and painting with frescoes of the church of St Nicholas in Kyriakoselia is associated with the local risings and the contribution of the Empire of Nicaea.

-

-

St Nicholas. Kyriakoselia. View from the NW (source: Sotiris Zapantiotis).

Following the Venetian conquest of West Crete, the region of Chania was divided into castellanies, roughly corresponding to the modern provinces. The Castellania Apicorno more or less matches today’s Municipality of Apokoronas. The fortified town of Castello Apicorno was built on the Kastelli hill, east of Kalyves. It was the administrative centre of the region and controlled the entrance to Suda Bay.

-

-

Ruins of Castello Apicorno (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

Although numerous villages of Apokoronas are mentioned in the Venetian sources, many are now ruined or completely destroyed. The location of some villages is confirmed by the existence of old churches, some of which date back to the second half of the 13th or the beginning of the 14th century. A typical example is the church of Panagia in Katomeri, Vamos, which was painted with frescoes in the second half of the 13th century and later operated as a small monastery near the village of Karydi Kartsomatado or Charcomatadho.

-

-

Panagia, Karydi. An angel from the scene of the Ascension (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

The ruins of the church of St George and other buildings in the village of Karydi date from the same period.

As far as the quality of art is concerned, in the mid-13th century, when the Venetians established themselves in the area of Chania, the island was cut off for a time from the influence of Constantinople and other artistic centres. As a result, local artists clung to the old models in a quasi-folk style. Typical examples of this trend can be seen in the works of Ioannis Pagomenos, a popular painter in West Crete. In Apokoronas, he painted the frescoes of the main church of the Panagia in Alikambos (1315) and the church of St Nicholas in Maza (1325).

-

-

Panagia, Alikambos. The donor Martha the nun (source: Michalis Andrianakis Archive).

Important paintings of the following periods can be found in churches scattered across the region. In the field of secular architecture, the forms of the Late Venetian period that predominated in Crete also prevailed in Apokoronas, as Mannerism replaced the older Late Gothic elements that had been incorporated into local tradition. The nobles, who divided their time between the city and their country properties, usually built luxurious villas connected to farms. An interesting example is the villa north of the Monastery of St George in Karydi with the nearby ruined olive mill, obviously associated with the local feudal lord.

During the Venetian period, important engineering works were constructed for the systematisation of agricultural production. In the village square of Kalyves, over the River Mesopotamos, is preserved one of the most important Venetian watermills in Crete, with five water inlets. Another watermill is located in Nio Chorio. The watermill of Kalogeroi was owned by the Monastery of Patmos and remained in use until recently. In Nio Chorio a fairly large villa survives in ruins, with many later renovations and additions. Of the infrastructure works of the Venetian period, a group of wells is preserved in the village of Gavalochori (link: Venetian wells in Gavalochori). The wells of the same period outside the village of Palailoni played a similar role in supplying the community with water. Yet another important industrial installation is found in the village of Gavalochori: an olive mill with a long period of use, as evidenced by the different grinding mechanisms preserved in situ.

-

-

Watermill, Kalyves. The east façade (drawing: Marianna Aggelaki).

These works illustrate the organisation of agricultural production by the Venetian state. On the fall of Chania to the Ottomans (1645), the region of Apokoronas became part of the Ottoman Empire. The Venetian castellany was transformed into a Turkish nahiye, still with its seat in Kastelli, as the fortress of Apokoronas (Castello Apicorno) would henceforth be known. At the same time, the institution of provincial governor (Kastel Kethüdasi) was established to represent the Christian population before the Turkish administration and collect the poll tax at the provincial level.

The new circumstances brought about serious changes in the life of the local inhabitants. Most of the land passed into the hands of the conquerors. Taxes were also particularly heavy, meaning that the former owners now became serfs. The abuses of the Muslims, particularly the Cretan converts to Islam, who oppressed the Orthodox population, also caused serious problems, encouraging the oppressed populace to convert in order to join the privileged class.

Agricultural production continued to be organised in the same way as in the previous period, and the same infrastructure often remained in use. Numerous mills survive in the area, some of them dating back to the Late Venetian period. Among the installations whose use began during the Venetian period and continued in Ottoman times is the Venetian-Turkish farmhouse in Nio Chorio.

In 1770 the Daskalogiannis Rising, led by Ioannis Daskalogiannis or Vlachos, broke out in Sfakia. The revolutionaries launched their operations from the nearby provinces. Apokoronas was directly or indirectly affected by every rising due to its location on the main road and its proximity to Sfakia, with which it had strong ties. The Daskalogiannis Rising was brutally suppressed and Daskalogiannis himself was captured and put to death in Heraklion, after being imprisoned and interrogated in the Tower of Alidakis in Embrosneros. A few years after the end of the rising in 1774, the great feudal lord, the Janissary Ibrahim Alidakis, was killed. His tower house is preserved in the village of Embrosneros).

-

-

Tower of Alidakis, Embrosneros. The building prior to its restoration (1972) (source: Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Antiquities of Chania).

At the time of the great Cretan Rising of 1866-1869, the province of Apokoronas was a prosperous one. On 20 July 1866, the representatives of the Cretan people gathered in Embrosneros once again and signed the first revolutionary declaration addressed to the Great Powers, announcing their decision to fight the Turks. The Ottoman fortress of Aptera (Subashi) and the fortress at Nio Chorio are monuments of this phase in the wider region of Apokoronas.

Many houses of the Ottoman period are preserved in Apokoronas. The Folklore Museum of Gavalochori is a typical example. It is an arch-house with an odas (bedroom) on the upper floor. The work towards the creation of an autonomous or semi-autonomous Cretan State began in Apokoronas and its centre, Vamos (the capital of what was then the Prefecture of Sfakia). The revolutionaries launched an armed struggle that ended in the siege of Vamos (3-18 May 1896), which had been the military, administrative and spiritual centre of the region since 1868. The events of this period attracted a great deal of international attention and contributed to the establishment of the Cretan State (1898-1913). In 1913 the island was united with Greece, going on to follow the historical course of the other regions of the country

A milestone in Greek history is the year 1922, when, following the Greek defeat in Asia Minor, the exchange of populations took place between Greece and Turkey. The “Turkish Cretans”, most of them Cretan Muslims, were forced to leave the island. They were replaced by Greeks who had also been forced to leave their homes in the Turkish territories.

After two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and a World War (1914-1918), the political situation in Greece was a desperate one. The successive governments occasionally sought to carry out reforms but without concrete results. The Vamos School, built around 1930, is the result of attempts to reform the education system and reflects the modernisation efforts of the Greek State in the interwar period.

Another major historical event is, of course, the Second World War. On 20 May 1941 the German airborne invasion (Operation Mercury / Unternehmen Merkur) began. The operation lasted until 1 June. The Germans met with strong resistance from the Cretans and their British and ANZAC allies. However, the Germans occupied the island and a period of brutality and terrorism of the local population began. As part of the military occupation of the island, the Germans constructed fortifications following contemporary practices. Among the German works of war are the Nazi Tunnels at Kokkino Chorio.

Resistance groups were organised in Apokoronas, as they were throughout Greece. A monument of the resistance against the Germans is a house in Asi Gonia, the headquarters of a local national organisation, the Supreme Committee of the Cretan Struggle. In Chania, the Occupation only ended 17 days after the end of the war, as the British believed that the German Army could safeguard their interests on the island against the onslaught of the Red Army. The Second World War was followed by the Greek Civil War (1946-1949) between the government army and guerrilla forces of the Democratic Army of Greece. In the following years, and especially in the 1960s, the countryside began to be abandoned with the wave of emigration to the United States, Canada, Australia and Germany, later culminating with the concentration of most of the country’s population in the urban centres.