In capitalist societies in the modern era there arose the idea of man the creator, a concept opposed to the millennia-old prevailing philosophy of man the steward. In pre-modern Western societies, God was the creator and the role of man was limited to maintaining the cosmic order. The concept of man as a steward is in line with the daily struggle against decay found in every aspect of human life, from preparing food to dusting the furniture. The prevailing perception of the replaceability of all material things, which is reflected even in modern approaches to the body, clashes with the principles of sustainability, which allow for the harmonious coexistence of man and his environment.

The present era is termed the Anthropocene, due to the fact that human activity is the main driver of climate change. The term is widely accepted despite criticisms and opposing views. The main counter-argument is that human activity has always caused environmental disasters on a larger or smaller scale. However, the rapid changes in lifestyle and human interaction with the environment in modern society are now affecting the geology and ecosystems of the planet in ways never before seen.

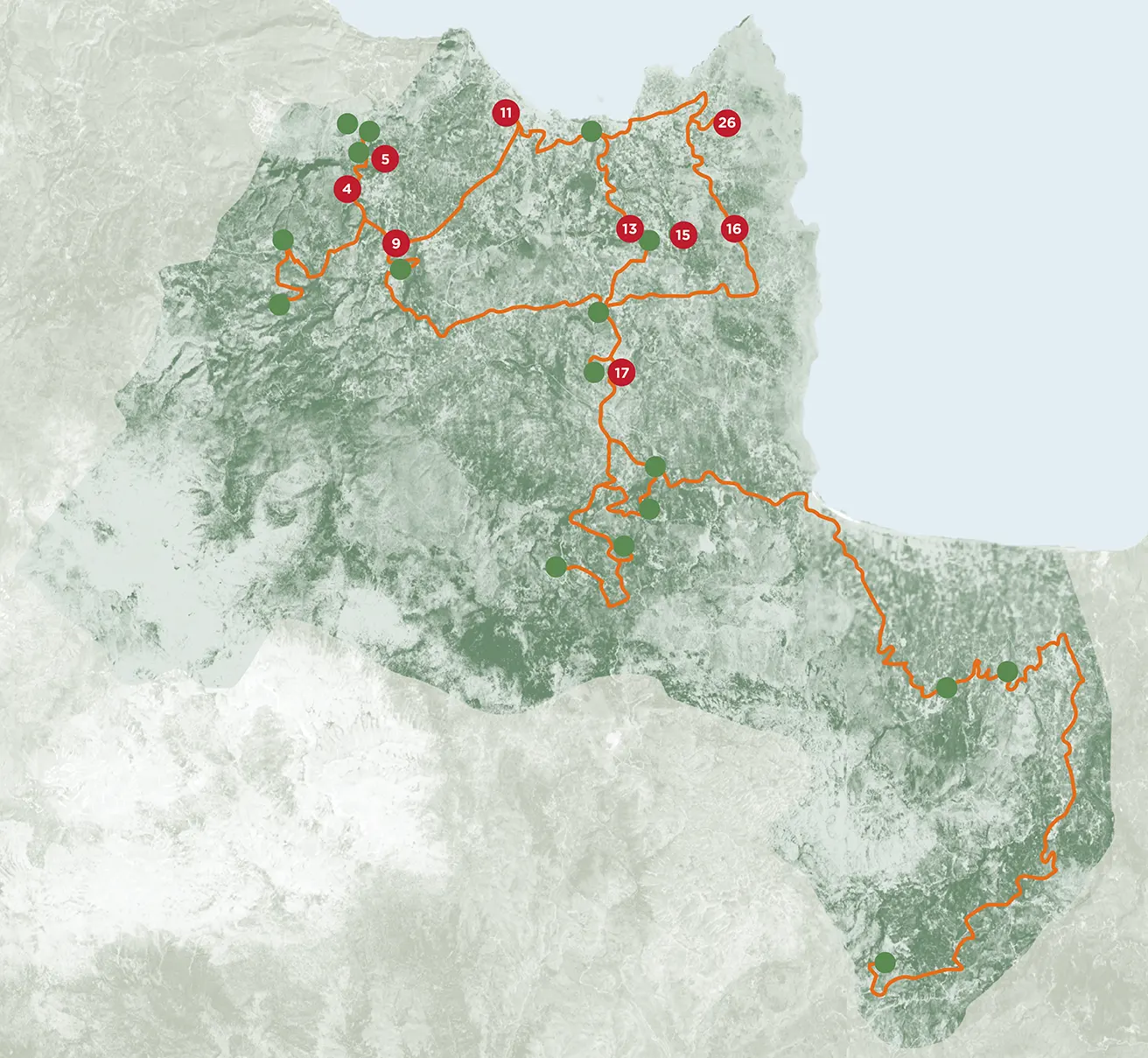

This route explores past practices that highlight principles of sustainable coexistence of humans and the environment, based on the perception of man as a steward rather than a creator.

In Apokoronas, a region with a varied terrain, rich in water resources and fertile soil and enjoying favourable climatic conditions, human activity flourished from an early date, leaving behind material evidence of man’s coexistence with his environment.

An important aspect of sustainability is the management of resources and practices by the community (tools to the people). People living in an area were able to manage their environment in the context of the community. Communalism played an important role in the management of natural resources in the region in the pre-industrial period. For example, the problem of limited water resources in part of Apokoronas was consistently addressed using collective solutions. The wells of Gavalochori and Palailoni were constructed in order to provide those communities with drinking water for people and their flocks. Dug in locations where rainwater could be collected, they were gathering places where members of the community could obtain water both for themselves and for their animals. Village fountains had a similar function, with people visiting them daily to draw water for their everyday needs.

-

-

Wells of various phases in the village of Gavalochori. The concrete wells were in use until modern times (source: Sotiris Zapantiotis).

-

-

Wells in the village of Palailoni (source: Sotiris Zapantiotis).

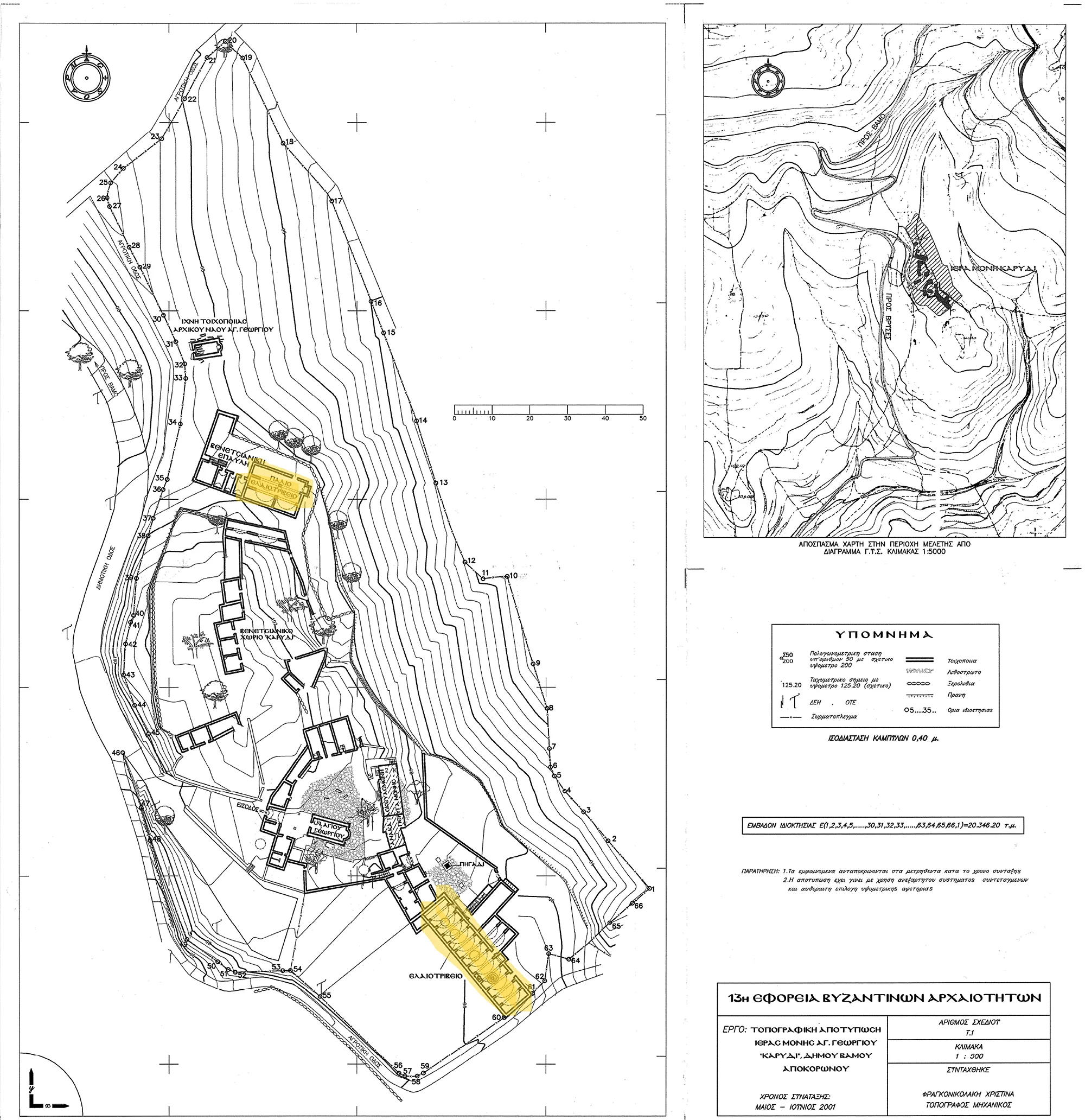

Communities were also bearers of knowledge on the management of the built environment. Thus local building practices were developed, based on the use of building materials available in the area. In the Apokoronas region, in villages such as Kefalas, there was an important tradition of stone masons in early modern times. Characteristic architectural types evolved in Crete. Still seen in villages today, they draw on elements of the Venetian and Ottoman past, the expertise of local craftsmen, the possibilities and limitations of the local building materials, and the different needs that arose over time. Ottoman mosques, the churches of the Ottoman period, the arch-houses and industrial buildings all have common elements, shaped by the environment of the island. It is interesting, for example, to compare the surviving olive mills of Gavalochori and St George in Karydi, where the system of wide arches for supporting the roof and dividing the space into “rooms” can be seen. The same arrangement is found in the arch-house of the Folklore Museum of Gavalochori, where a wide arch divides the house into separate areas for different activities.